Should ESG Investors Own Cryptocurrency?

The growing popularity of cryptocurrency has created a new wrinkle for investors—how to balance its potential upside against its inherent environmental and social impacts. A look at both sides of the issue.

Originally published on Morgan Stanley Insights

Despite the recent exponential growth in the cryptocurrency industry, this emerging asset class leaves many open questions for investors who integrate environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues into their portfolios.

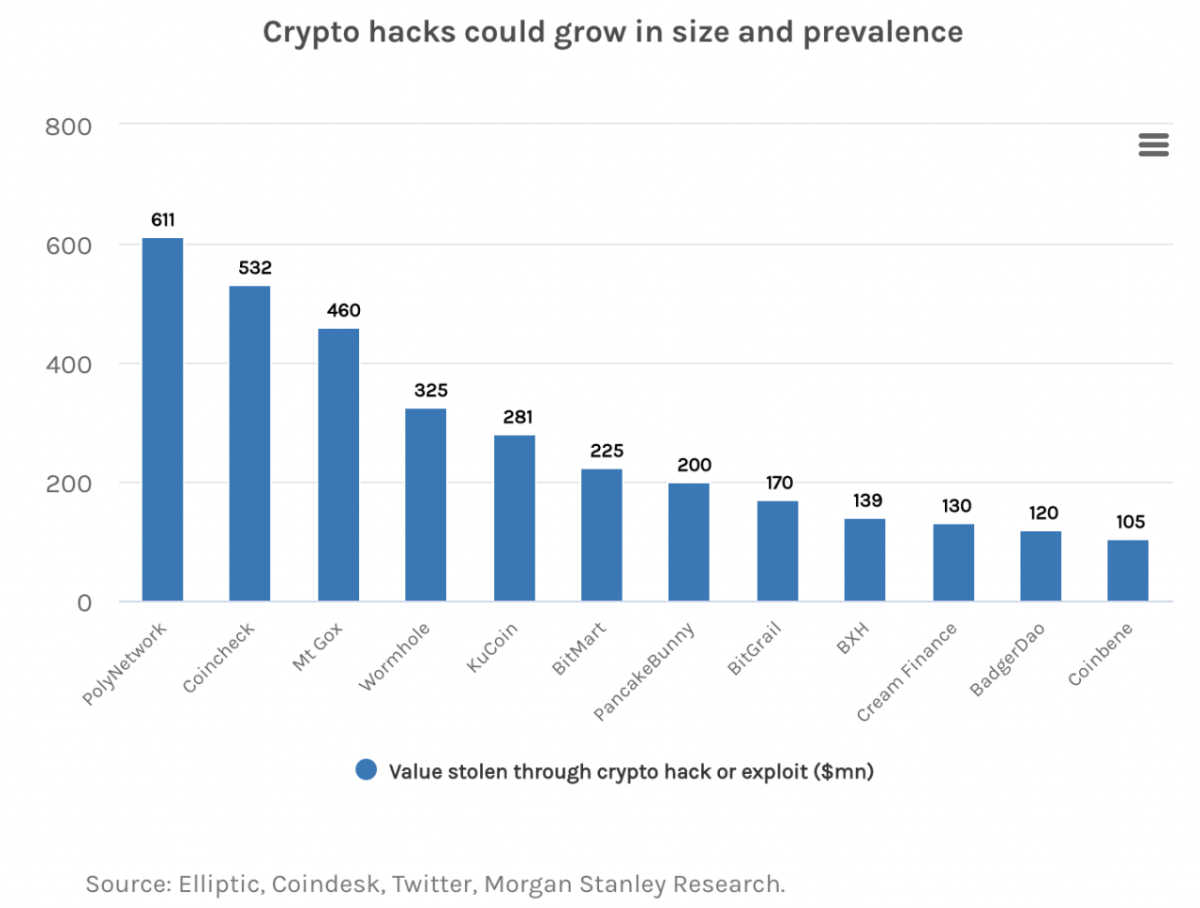

While crypto can offer some societal benefits—such as financial inclusion and the ability to “be your own bank”—there are also potential downsides, including its carbon footprint, prevalence of theft through hacks and lack of centralized governance.

These issues are being hotly debated within the crypto community, as well as by policymakers, corporations and other entities around the world. Investors, for their part, should consider the nuances of individual digital currencies and weigh the pros and the cons in the context of their own sustainability goals.

As a key first step, Morgan Stanley’s Cryptocurrency and Sustainability Research teams did a deep dive on the key ESG issues surrounding this asset class. Here’s what they found.

Calculating Carbon Intensity

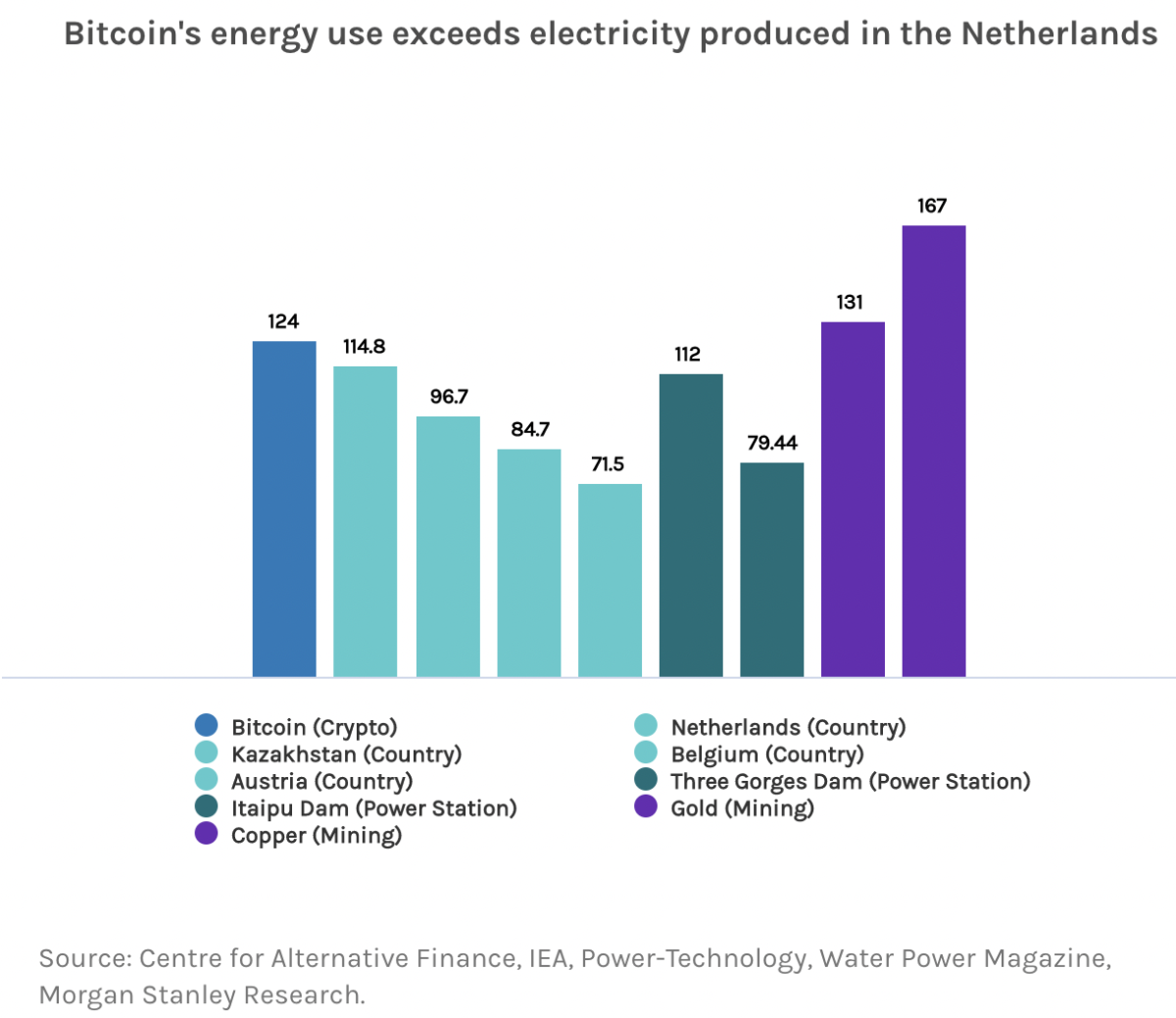

There is almost no escaping the fact that crypto requires a lot of energy-consuming computing power to create and verify new transactions on the blockchain—a process known as “mining.” The annual energy consumption of Bitcoin, for example, is equivalent to the total electricity produced in the Netherlands.

“Every $1 of Bitcoin mined is materially more carbon intensive than every $1 of gold mined,” says Jessica Alsford, Global Head of Sustainability Research. Put another way, her team estimates that Bitcoin's carbon intensity was 14.2 million times that of a Visa Credit Card transactions

Of course, many variables affect the carbon intensity of maintaining the cryptocurrency network, including how new transactions are validated. For example, the “proof of work” process used in Bitcoin requires significantly more energy than the “proof of stake” that the world’s second most prominent cryptocurrency, Ethereum, is hoping to adopt later this year.

And many crypto mining companies are using renewable sources of power and have committed to carbon offsetting. Still, it’s a tall order. “We estimate that powering Bitcoin's yearly energy requirement via green energy would require the equivalent infrastructure of the entire U.S. solar fleet,” says Alsford. As long as Bitcoin and other crypto mining is profitable, the energy requirements will continue to increase over time but may use energy from increasingly greener sources.

What may be more critical: Concerns about crypto’s environmental impact are more than a matter of social responsibility. “We see continued risk of governments restricting energy use for crypto mining,” says Sheena Shah, Morgan Stanley’s lead Cryptocurrency analyst. She notes that many countries, including China, have banned crypto mining, while others have restricted it.

“Mining bans are unlikely in developed markets, but the U.S. government has debated the climate impact and some EU representatives have proposed prohibiting energy-intensive crypto mining,” she adds.

Weighing Social Pros and Cons

Despite the energy demands of Bitcoin, many of the qualities that make it an attractive currency alternative go hand-in-hand with its real societal benefits, such as greater financial inclusion.

“Cryptocurrencies could be one way to increase access to financial systems for the unbanked,” says Alsford. “Anyone with a smartphone or laptop and internet connection can access cryptocurrencies, which arguably is a lower requirement than that of traditional bank accounts.”

In addition, cryptocurrencies can support faster and more affordable cross-border transactions—specifically, giving people an easier way to send money to relatives in other countries— and may be a better alternative in countries with volatile or depreciating local currencies.

But while crypto could open doors for greater financial inclusion and the ability to transact without intermediaries, it’s also a popular payment option for illegal activities.

Academic researchers estimate that between January 2009 and April 2017, 46% of Bitcoin transactions were linked to illegal activity, to the tune of $76 billion, which is equal to the U.S. and EU illegal drug markets. There is a counterpoint: Other estimates of illegal activity across all cryptocurrencies paint a different picture. In 2021, an estimated $14 billion of cryptocurrency, or just 0.15% of crypto volume traded, was associated with criminal activity.

Understanding the Role of Governance

Most cryptocurrencies use blockchain networks that are decentralized databases of transactions where no single entity makes or enforces regulations. Anyone can create a new cryptocurrency, and, in fact, the world still doesn't definitively know who invented Bitcoin.

At first glance, this seems to defy good governance and raise myriad questions, including: Who makes the rules related to how a cryptocurrency operates? Is there a board of directors? Does the cryptocurrency or its applications always comply with the law?

Of course, proponents of cryptocurrency argue that such decentralization is the definition of good governance, precisely because no single entity has control.

For their part, the analysts covering cryptocurrency and sustainability at Morgan Stanley believe that new crypto regulations are likely to change the rules of investing in crypto-related products. Whether that simplifies the complicated nature of the asset class for sustainability-focused investors, however, seems unlikely, at least in the short term.

For more Morgan Stanley Research on ESG consideration for cryptocurrency, ask your Morgan Stanley representative or Financial Advisor for the full report, “Sustainability and Cryptocurrency: ESG Considerations” (February 22, 2022) Plus more Ideas from Morgan Stanley’s thought leaders.

Important note regarding economic sanctions. This research references country/ies which are generally the subject of comprehensive or selective sanctions programs administered or enforced by the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (“OFAC”), the European Union and/or by other countries and multi-national bodies. Any references in this report to entities, debt or equity instruments, projects or persons that may be covered by such sanctions are strictly informational, and should not be read as recommending or advising as to any investment activities in relation to such entities, instruments or projects. Users of this report are solely responsible for ensuring that their investment activities in relation to any sanctioned country/ies are carried out in compliance with applicable sanctions.