Four Mutual Fund Giants Begin to Address Climate Change Risks in Proxy Votes: How About Your Funds?

Nearly all climate scientists and every government on earth (except for one) agree that society faces profound risks from human-induced climate change. Does your mutual fund company, investment manager, or 401(k) manager agree that the risks are serious and extend to companies in their portfolios?

For an overview of risks to businesses from climate change and what they should disclose, see reports and recommendations of the Financial Stability Board’s Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosure (TCFD), Chaired by Michael Bloomberg, former Mayor of New York City. Examples of these risks already translating into impacts include the record-breaking string of Atlantic hurricanes and wildfires in North America. Opportunities include the plummeting prices and explosive growth in renewable energy and electric vehicles globally.

Warren Buffett wisely notes: “Only when the tide goes out do you discover who’s been swimming naked.” But we now know the tide is coming in, literally and metaphorically, as seas rise and rain falls in feet instead of inches. The risks from climate change to financial markets and companies are widespread. As the credit rating agency Moody’s recently warned, even municipal bond investors and issuers have plenty to worry about related to the changing climate.

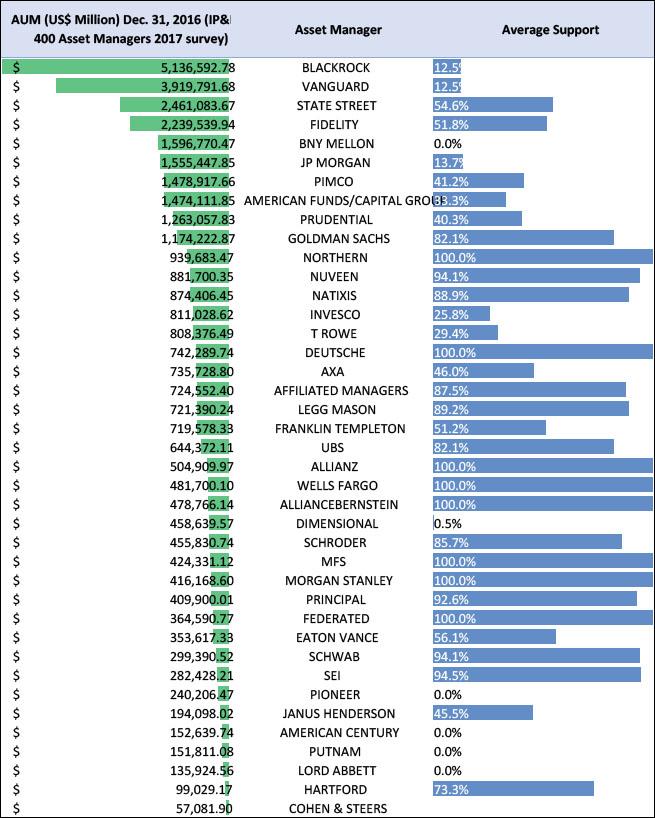

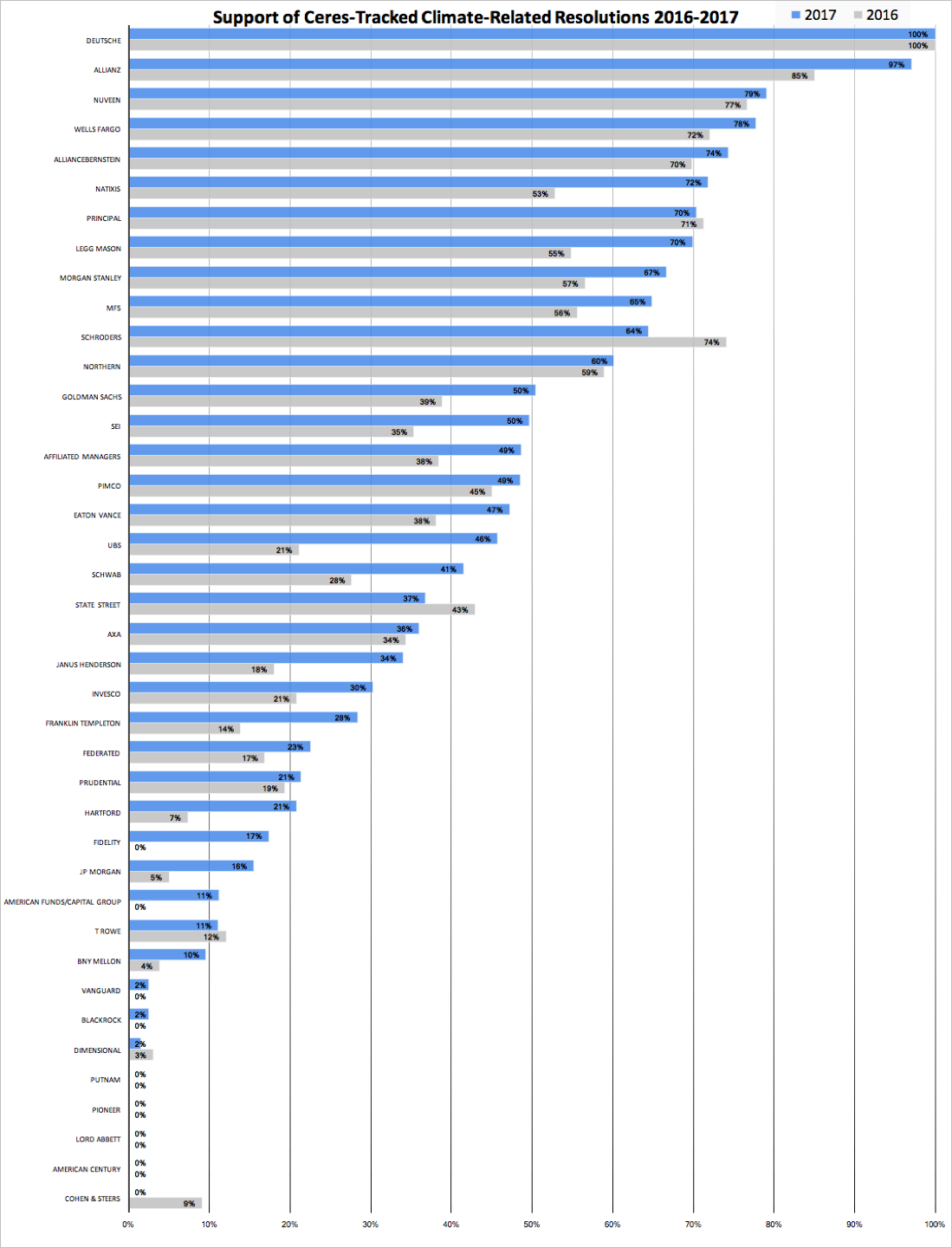

Each year, Ceres partners with Fund Votes to rank the largest mutual fund companies based on how strongly they support climate-related shareholder proposals. (See methodology note at the end of the blog for more details.) The results for 2016 and 2017 are shown in Table 1, and the big news is that four of the top ten largest asset managers, together accounting for $12.8 trillion in assets under management, voted for a climate proposal for the first time ever. This has important implications.

All mutual fund companies have to vote on climate-related shareholder proposals annually. It is their legal fiduciary duty to vote guided by what is in their client’s best financial interests.

Since many of the shareholder proposals ask companies to disclose climate-related risks and / or risk-mitigation strategies, a mutual fund company that votes against most or all of the proposals is vulnerable to accusations that it is ignoring or denying the impact of climate change on business and the global economy in its analyses to determine how it votes its proxies. (And if money managers ignore these issues in proxy voting, might this mean they ignore them while investing?)

So it is remarkable that in 2017 five money management firms still failed to vote in favor of a single climate-related proposal: American Century, Cohen & Steers, Lord Abbett, Pioneer, and Putnam.

By voting this way, these firms are signaling they believe it is in their clients’ best interest if the companies in their portfolios avoid disclosing the profound and far-ranging risks related to climate change and opportunities tied to climate solutions. This approach defies common sense. In last year’s blog on mutual fund proxy voting we explore the possible explanations – each of them inadequate -- for this voting behavior.

The bigger news in 2017 is which big asset management firms voted for the first time ever “for” a climate-related proposal. The first-timers (and their global size ranking according to assets under management) are: BlackRock (1), Vanguard (2), Fidelity (4), and American Funds (8).

The sleeping giants of the mutual fund industry are waking up to climate risk. We see this in their proxy voting, in their engagements / dialogues with companies where they raise climate risk, and in their public statements and relevant background papers. Climate risk is now truly recognized as a mainstream issue impacting financial risk and return.

What are the practical implications of the largest asset managers voting for climate-related shareholder proposals? Higher votes, and even majority votes on climate-related proposals, are now much more likely because these 4 asset managers collectively own around 10%-15% of many companies’ shares.

Indeed, 2017 produced the first majority votes ever on climate change shareholder proposals at oil and gas companies and electric utilities. The proposals requested that the companies issue analyses of the business impact of a scenario in which global average temperatures are kept from rising more than 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. The shorthand name for these are ‘two degree scenario’ (2DS) proposals. (As part of the Paris Agreement, all countries agreed to limit global average temperature rise to “well below” 2 degrees Celsius. The U.S. is still technically signed-on to the Agreement at least until Nov 4, 2020, one day after the next presidential election.)

The majority votes in 2017 on 2DS proposals were: 62.1% at ExxonMobil, 67.3% at Occidental Petroleum, and 56.8% at electric utility PPL Corporation. While not legally binding, majority votes put enormous pressure on companies to address the issues raised in the resolution. It is a particularly dangerous move for a company’s board to ignore a majority of their shareholders. Even votes above around 25% apply significant pressure on companies to address the request made in the proposal.

On December 11th, 2017, Exxon agreed to issue the disclosure requested by the proposal that received the majority vote last spring, which was filed by the New York State Comptroller’s Office and the Church of England, and backed by investors with over $10 trillion in assets under management.

ExxonMobil’s new disclosure will be issued in the context of a large and rapidly expanding pool of solid empirical evidence showing that environmental and social megatrends like climate change can affect financial performance. Many of the biggest global investment management firms already see this connection and ask companies in their portfolios to disclose and address the risks. This is a significant signal to companies from their owners that they must take action to address climate-related risks and opportunities.

Despite the positive momentum and excitement among investors created by these majority votes, let us add some words of caution, putting the majority votes in context.

During the 2017 proxy season, approximately 90 climate-related shareholder proposalswent to a vote at company annual meetings. The proposals requested that companies act on a variety of issues including setting greenhouse gas reduction goals, reducing methane leaks, and issuing sustainability reports. Seventeen of the proposals requested a 2DS analysis. Table 2 shows the percentage of these resolutions that each of 40 largest asset managers voted “for.”

BlackRock and Vanguard each supported only two of the resolutions (both voted “for” the proposals at ExxonMobil and Occidental Petroleum.) And these were the only climate-related proposals (out of 90) that they supported.

So, while it was an important breakthrough for two of the largest asset managers to finally vote for climate proposals, their clients and other investors should continue to urge these firms to speak out publicly and vote in support of other climate-related shareholder proposals where there is a strong business case.

In fact, pressure from their own shareholders and clients may have played an important role, along with the mainstreaming of climate risk in financial markets (e.g., see reference to TCFD above) in convincing both BlackRock and Vanguard to begin to vote for climate resolutions. Both firms received shareholder resolutions in 2017 filed by Walden Asset Management requesting a review of proxy voting on climate change. Walden withdrew both proposals in return for commitments by the companies to address the request.

So far during the 2018 proxy season, three resolutions have been filed with mutual fund companies requesting a review of proxy voting policies: Bank of New York Mellon (filed by Friends Fiduciary), Cohen & Steers (filed by Walden Asset Management), and T. Rowe Price(filed by Zevin Asset Management).

Tim Smith, Director of ESG Shareowner Engagement at Walden Asset Management, noted: ”We believe the recent voting changes by major mutual funds and investment firms signal an expansion of their climate change engagements with companies where they own shares. Meanwhile those mutual funds and investment managers that are just beginning to use their voice and vote will inevitably be pressed by their own investors and clients to be much more active leaders.”

Another leader engaging large asset managers on their proxy voting on climate risk is Pat Tomaino, Associate Director of Socially Responsible Investing at Zevin Asset Management. He put it this way: “The risk of climate change to investment portfolios is clear as day, confirmed by science and developed by blue-ribbon commissions. Now investors must act on that information — by reaching out to companies, by communicating with the public on climate change, and by consciously voting on reasonable shareholder proposals that urge companies toward progress and transparency. In short, the big investment companies need to step up and make judicious use of every tool in the toolbox to address climate change.”

Jackie Cook, founder of Fundvotes.com, concludes: “Large asset managers wield considerable power with their proxy votes. This should be trained on avoiding climate-induced catastrophe in capital markets by promoting climate-related financial disclosures and strong board-level climate competence.“

Methodology

Support by each asset manager shown in Tables 1 and 2 is calculated by computing, for each fund run by an asset management company, the percentage of votes “for,” “against,” or “abstain” for each resolution. The support levels by each fund are then averaged across the family of mutual of funds (or other investment vehicles) offered by the asset manager to derive their overall level of support for the Ceres-tracked climate-related resolutions voted on by the asset manager during each proxy season.

The method just described is slightly different than what we used last year. As a result, the 2016 support levels shown in Table 1 differ in minor ways for a few firms from the support levels we published last year. The change addresses situations where an asset management firm voted in different ways for the same resolution — for example one mutual fund voted “for” while another mutual fund within the same firm abstained. Last year, if 75% or more of funds within an asset management firm voted “for” a resolution, then that firm was considered to have voted “for" all of those resolutions.