Financing a Net Zero Economy: Banks Must Grapple With Asset-level Data

By Dan Saccardi, Program Director, Ceres Company Network; Blair Bateson, Director, Ceres Company Network; and Tamar Aharoni, Senior Associate, Ceres Company Network

Technical Analysis by FutureProof

As the lynchpin of the global economy, financial institutions not only carry a responsibility to help mitigate climate change, they are also vulnerable to its financial risks. The SEC has recently recognized this in their proposed rule requiring financial institutions to report on climate risk in financial terms.

That climate risks are systemic risks for banks is clear. Over the past two years, Ceres has published reports quantifying the impact banks face from two main risks—the risk the companies in their portfolios face from a delay in transitioning to a clean economy and the physical risks of a warming planet that those companies are exposed to. Our 2021 analysis of the physical risks of climate change, from extreme storms to droughts, estimated that the banks’ climate value-at-risk for their syndicated loans could amount to more than $250 billion annually by 2080.

For banks, a critical step to addressing the climate risks within their portfolios is quantifying these risks. The top-down analysis that we did in our reports covers a specific piece of the biggest U.S. banks’ portfolios—syndicated loans—allowing us to provide a framework for the kind of comprehensive analysis needed to understand the risks being unleashed by climate change.

But this top-down analysis is comparable to quantifying just the tip of the iceberg. The “non-visible” portion of physical climate risk is still submerged in deep waters—in particular, the assets of the clients that banks finance. Understanding that portion of climate risk requires a different kind of analysis—a bottom-up analysis using data that only the banks have. Banks need to analyze the asset-level exposure of the clients that they finance to appropriately expose the magnitude of physical risks that financial institutions face from climate change.

In our report on physical risk last year, we explored how this bottom-up analysis of asset-level data might be done, but we did not have the data to fully conduct such an analysis. Building on that work, we and climate analytics firm FutureProof developed an approach that uses one of the few publicly available asset-level data sets: banks’ physical offices and branches.

Of course, the most material physical climate risks that banks are exposed to come from a more indirect source: the clients they finance and the physical risks those entities face. But since this kind of client data is not publicly available, we modeled the banks’ own physical offices and branches as an example of the type of asset-level, client-focused analysis banks need to do. By applying this kind of asset-level evaluation to their clients’ physical risk exposure, banks could react to these risks by anticipating the scope of losses, pursuing ways to minimize them, and investing in climate resiliency measures to benefit their bottom line and affected communities.

A prototype for bottom-up analysis

Analyzing a sample of over 20,0001 banks, we projected climate-linked financial losses – in the spirit of the SEC’s proposed requirements – at banks’ facilities throughout this century from hazards including floods, hurricanes, wildfires, tornados, hail, snowstorms, wind, and lightning. For flood losses specifically, our projections in this report are based in part on combining flood maps, flood event sets (including climate-altered event sets) and software from the modeling firm, KatRisk, with FutureProof’s proprietary methods for translating this to financial losses.

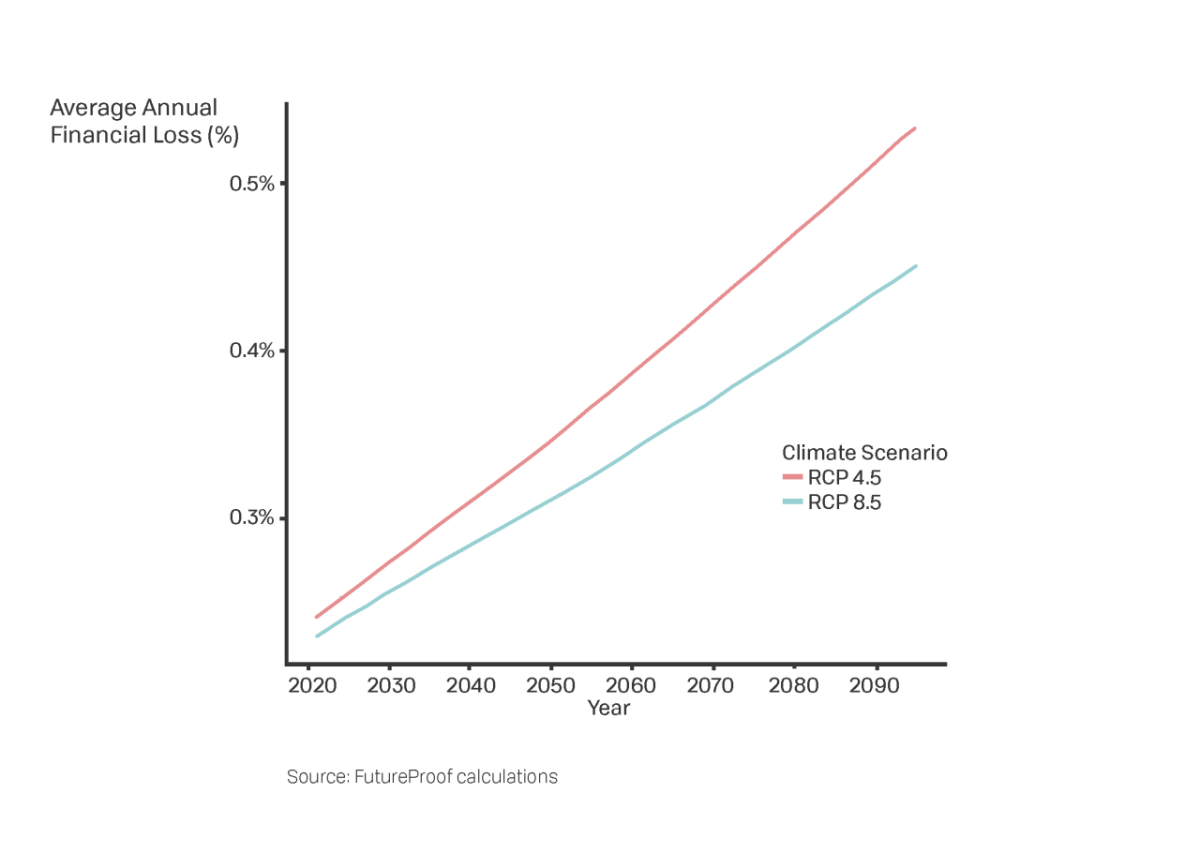

Figure 1 illustrates this analysis. This analysis is a proxy, at least in a qualitative sense, for the physical climate risk to banks’ broader portfolios. In the absence of better data, it may be reasonable to assume that the geographic concentration of banks’ facilities is like that of their broader portfolios.

Our analysis used two different climate scenario models that are laid out in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) AR5 reports and imply certain levels of carbon emissions and temperature rise. Even when looking at the less disruptive scenario (RCP 4.5, see Figure 1 caption), average projected losses rise significantly over the remainder of the 21st century, from 0.23% of the value of the assets in 2021 to 0.31% by 2050 and 0.46% in 2099. If, for example, a bank has a $100 million facility, this implies that it will on average suffer $460,000 in average annual losses due to climate-related factors by 2099. This would rise to $550,000 (0.5%) in the worst-case scenario (RCP 8.5).

Who is at greatest risk?

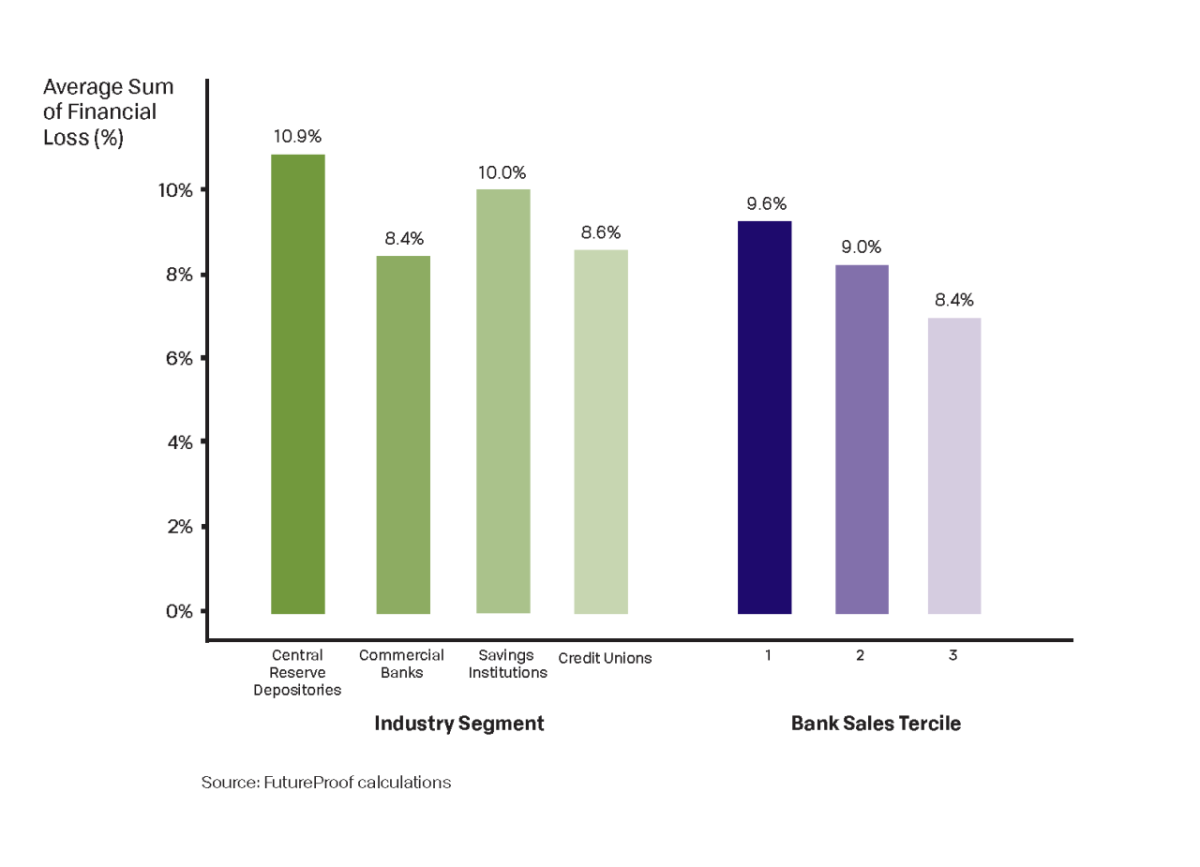

Such losses can vary by type of bank, which we explored across two dimensions: industry segment and size (revenue tercile).

Figure 2 shows that while impacts vary, no industry segment escapes significant losses. Looking at size, the analysis shows that higher-revenue banks tend to have lower climate-linked losses. One possible explanation is that these banks are able to locate their facilities in areas with more climate resiliency measures. Another potential cause is simply the fact that larger banks are more geographically diverse.

A tale of two banks

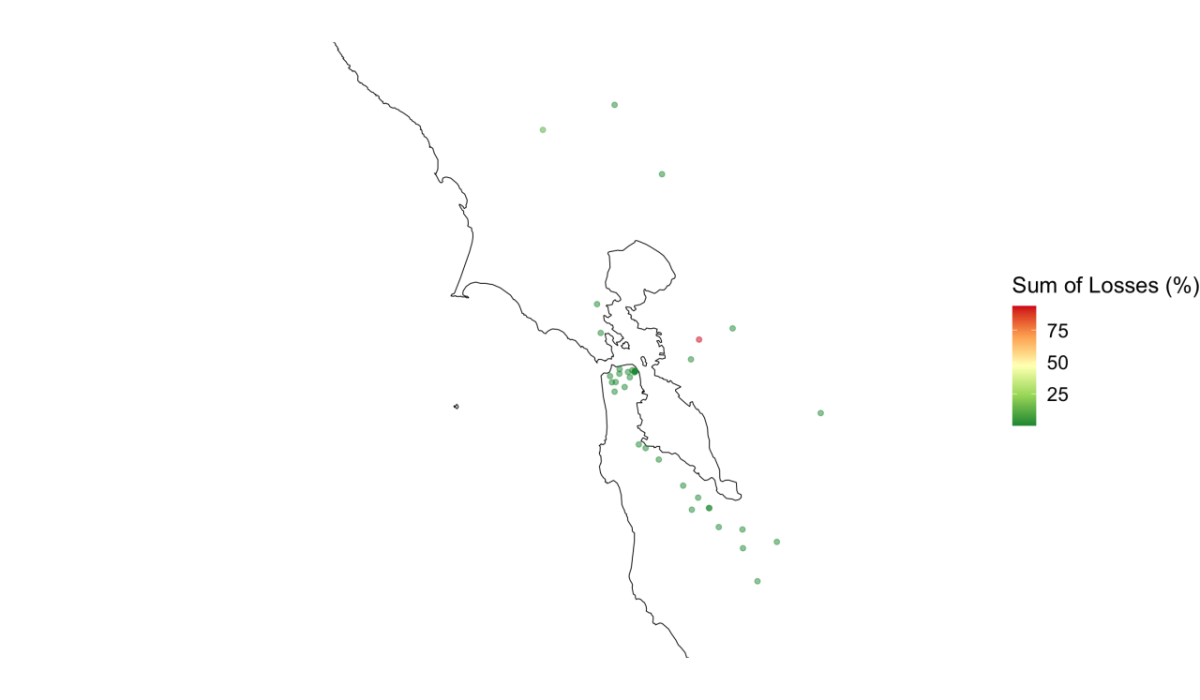

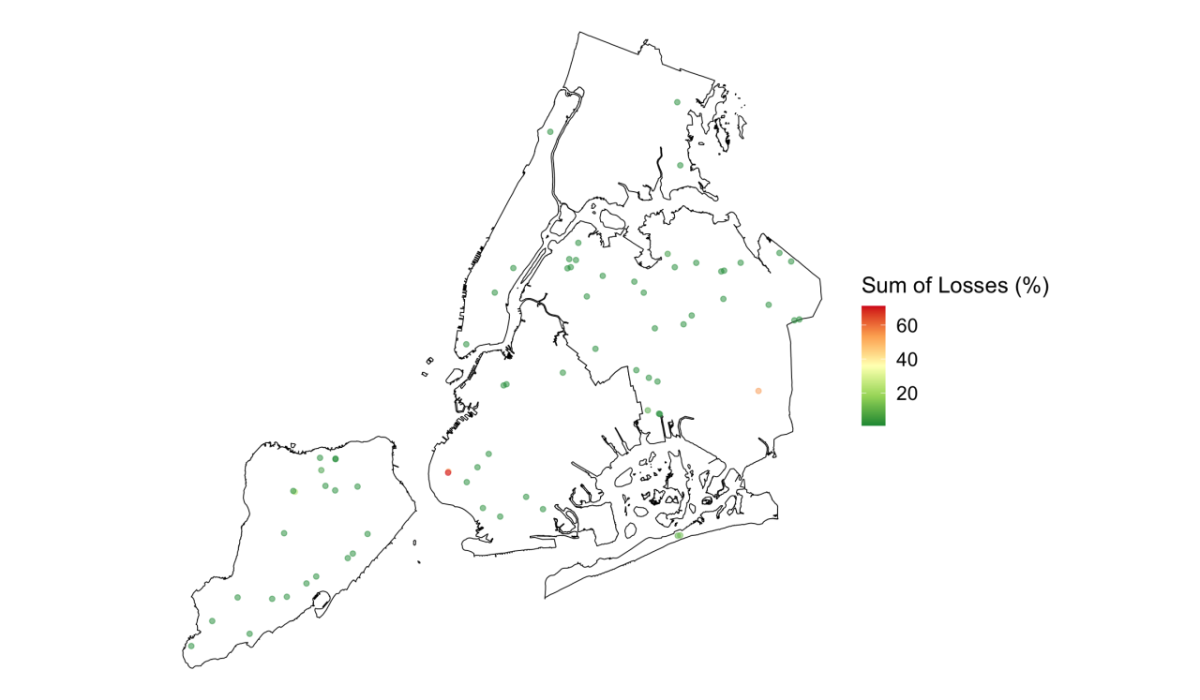

To set the data in context, we profiled two actual banks (though kept their identities anonymous): bank A, largely based in the San Francisco Bay Area, and bank B, largely based in the New York City area. We chose to compare these two banks because of their geographic concentration – such concentration means that the risk to their facilities may more closely mirror the more material risks posed by their clients’ physical risk exposure.

Bank A’s Bay Area losses stem primarily from flood and wildfire risk. Losses to Bank B’s NYC branches, by contrast, are due primarily to flood and hurricane risk. Both banks face relatively low climate risk compared to our overall sample average, though even for them our analysis found that specific branches face significant and increasing climate risk.

What should banks do next?

As a proxy for the physical climate risk to banks’ broader portfolios, our analysis of banks’ facilities can be seen as a lower bound on the losses banks will face from physical climate change (because we only used data on banks’ own facilities and not those of their clients). That gap underscores the importance of the banks conducting a comprehensive, asset-level evaluation of physical climate risk. Unfortunately, such data is currently still limited. As a first step, banks would need to implement a process for collecting the relevant data from their clients as part of the lending process, as insurers do. This information will be critical for evaluating individual client relationships and potential transactions. Banks must address this challenge to fully understand their exposure to and prepare for future climate events, which are only increasing in frequency and severity. The proposed rule from the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) on mandatory corporate climate disclosure is an important signal that the market is moving toward regulating disclosure of corporate data. However, far more granular data is needed to perform this asset-level analysis, so banks cannot simply rely on the SEC.

The projected losses in our analysis—and what they imply in terms of greater risks for banks—are not inevitable. They can be reduced if banks become more climate resilient. Adaptation is a critical and often neglected avenue for reducing exposure. Addressing asset-level climate risks should be seen as a potential opportunity for banks to create significant new value for their institutions, their clients, and the broader economy.