Smarter Technology Is Turning Deadly Venom Into Potential Medicine

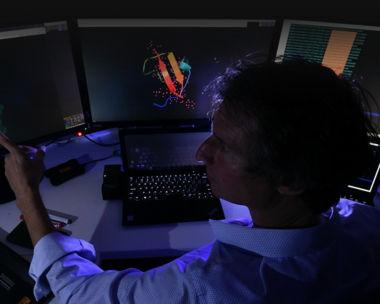

Dr. Zoltan Takacs uses a ThinkPad to analyze some of the world's deadliest toxins and turn them into medicine leads.

Most people avoid venomous creatures. Dr. Zoltan Takacs has spent his life chasing them.

The renowned scientist and explorer seeks out the venoms of some of the world’s deadliest creatures — snakes, spiders, scorpions and more — with the hope that their lethal toxins will provide a template for designing new medicines. The basic logic behind his method: What can kill you just might save your life.

About 20 medicines are already derived from animal venom toxins, including two of the top drugs used to treat heart attacks. Other animal venom toxins are being used to treat a host of diseases such as high blood pressure, heart failure, thrombosis, diabetes and chronic pain associated with cancer and HIV. The molecular structure of these lethal toxins has evolved over millions of years to bind to and modify specific receptors that command vital life functions. Researchers hope to harness this evolutionary wisdom to develop medicines that bind and modify only that receptor that is linked to the disease, thereby reducing side effects and increasing therapeutic success.

Takacs’ research and passion has taken him to more than 190 countries. He’s been bitten by snakes half-a-dozen times and has become allergic to both venom and anti-venom. But the Hungarian-born biomedical scientist is driven by the knowledge that potential life-saving medicines may be hiding in the venom of creatures found in the most remote corners of the earth. That, and his lifelong passion for exploration. Beyond his scientific pursuits, Takacs is an aircraft pilot, scuba diver and avid wildlife photographer.

The Hungarian-born biomedical scientist is driven by the knowledge that potential life-saving medicines may be hiding in the venom of creatures found in the most remote corners of the earth.

Takacs’ fascination with the natural world is lifelong. As a child, he recalls catching “all kinds of snakes,” including his first viper at 14, and bringing them home. “I always knew I wanted to be a scientist,” he says. What drives him is “the mystery and beauty in life.”

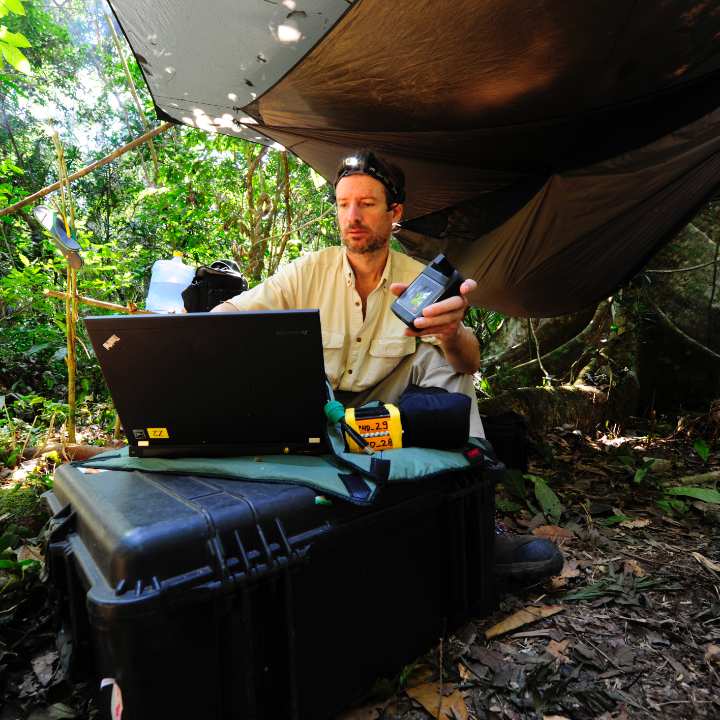

It can take months of planning, travel, and searching before Takacs locates his target, from securing permits within the host country to actually sighting the animal of interest. Once he finds the venomous creature, Takacs captures it, takes a small tissue sample, and typically sets it free.

While in the field, the scientist is able to carry only a carefully selected cadre of equipment, which always includes his Lenovo ThinkPad, powered by Intel® Core™ processors.

“Everything besides catching a snake requires a computer,” the longtime ThinkPad user says of his work. But he corrects himself: “Well, even catching a snake requires a computer to email the permit application…”

Takacs relies on Lenovo’s innovative technology solutions for executing every aspect of his trip: planning, GPS navigation, labeling samples and storing data. In a pinch, he’ll charge his devices with car batteries and solar power.

“It doesn’t matter where we travel — I have to have access to my data and have the ability to work with it,” he says. “All of this is done with Lenovo machines.” For Takacs, choosing the right technological equipment comes down to “portability, reliability and powerful specs.”

But powerful specs only get you so far when you’re tromping through the Congo rainforest for days at a time. In these conditions, Takacs requires his equipment to be not only mobile but tough — from the boots on his feet to the laptop in his backpack.

“I have Lenovo computers from a decade ago. All of them are still working, and I’ve been traveling with them literally the entire world,” he says. And travel for Takacs is hardly the standard weekend getaway.

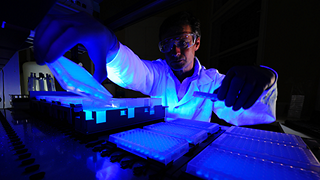

Innovative technology also comes into play back in the lab, where Takacs currently employs upwards of four Lenovo machines that help him to facilitate his scientific vision. After acquiring a sample, Takacs takes it to his laboratory where he and a team of researchers extract the toxins’ genetic blueprint and use the data to design and build Designer Toxin libraries. Then, supported by high-throughput technologies, he screens these libraries for novel medicine leads.

After acquiring a sample, Takacs takes it to his laboratory where he and a team of researchers extract the toxins' genetic blueprint and use the data to design and build Designer Toxin libraries.

Developed by Takacs and colleagues at the University of Chicago, the libraries of the Designer Toxin platform contain over a million animal toxin variants aimed at one particular receptor type. The toxin variants are engineered by computational genomics and molecular modelling based on natural template toxins. In fact, they are “mosaic toxins,” meaning various parts of the toxin are pasted together from different kinds of venomous animals. To analyze the data, Takacs and his colleagues use computational methods — powered largely by Lenovo’s ThinkPad machines — to screen the toxin variants on key receptors, thereby determining which toxin is likely to best treat the disease of interest.

The Designer Toxins library has already resulted in drug lead molecules, though it may take over a decade of testing and trials before the findings reach the consumer market.

Advancing technology is a key aspect of Takacs’ mission. “Toxins rank among the most sophisticated and powerful for finding key receptors in the body,” he says. “On the one hand, we want to maintain this natural wisdom. On the other, by applying pharmacology to bioinformatics, we are using cutting-edge technology to improve on what nature has achieved in hundreds of millions of years of trial-and-error.”

Takacs has a long list of destinations he hopes to visit — Asia and Africa are next on his list — though research priority, permits and seasonal time-windows are key to his planning process. Alas, with more than 150,000 venomous animal species currently roaming the planet having an estimated arsenal of 20 million toxins, one can be assured the scientist won’t run out of research and explorations anytime soon.