The Evolution of Project Delivery: The How and Why

Nontraditional delivery methods are gaining ground when commissioning large-scale water projects

There are an estimated 240,000 water main breaks every year in the United States, and those ruptures waste between 14 percent and 18 percent of the nation’s drinking water. Aging infrastructure is primarily to blame, as an estimated 40 percent of U.S. water and wastewater pipes are beyond their life expectancy, notes a recent article in WaterWorld.

The article goes on to say that half of forecasted capital expenditures by water providers will cover new installation and rehabilitation of underground infrastructure. In other words, utilities have plenty of large projects ahead: new pipelines, sewer lines, water and wastewater treatment plants, pump stations, reservoirs and more. In commissioning these initiatives, nontraditional delivery methods are gaining ground.

Download the full 2019 Water Report

Results from Black & Veatch’s 2019 Strategic Directions: Water Report survey show that water providers are looking at new ways to get big jobs done.

Signed, Sealed, Delivered

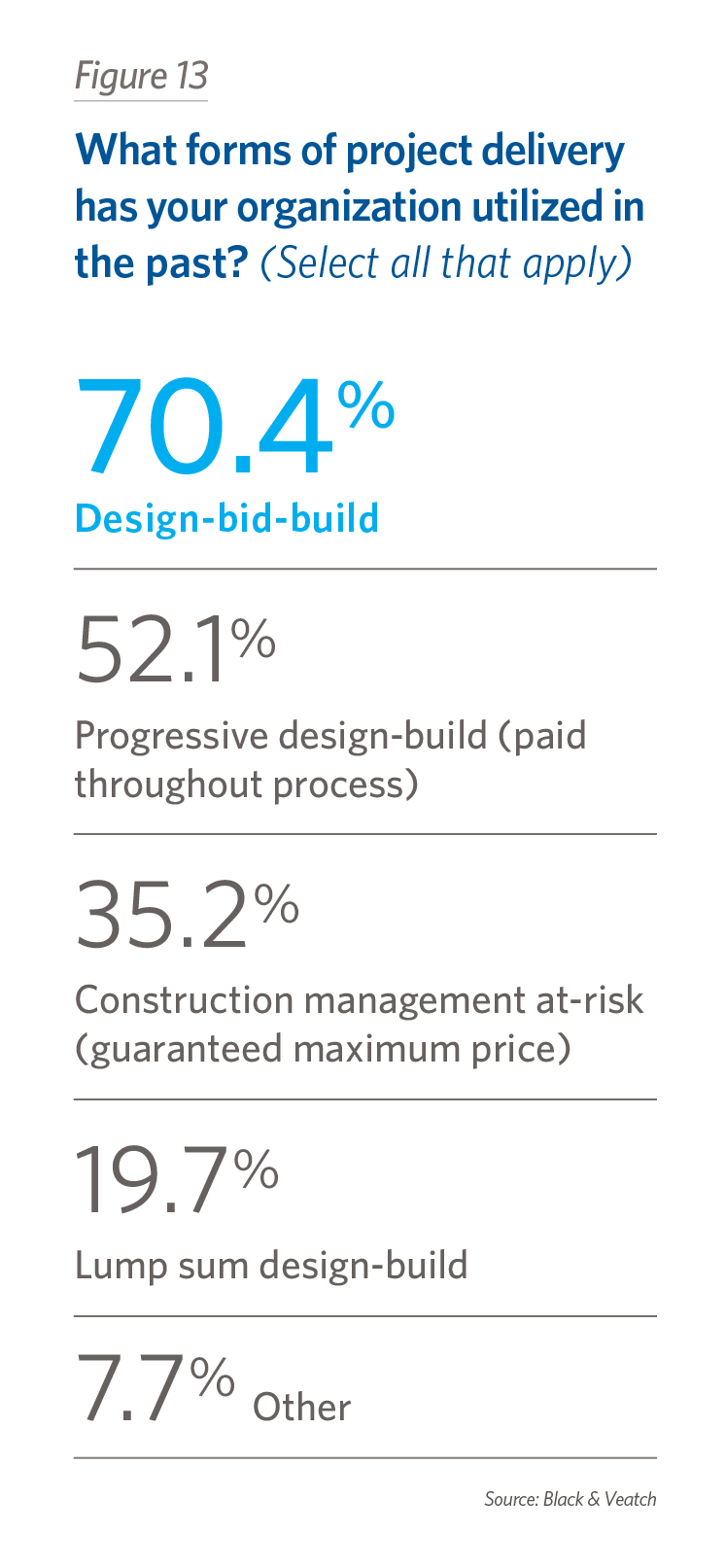

This year’s survey asked water utility staff to share their views on four methods of project delivery. Design-bid-build (DBB) is the most common approach to getting projects done. This delivery mechanism gives the utility a guaranteed maximum price based on the plans and specifications presented by the utility when it solicits bids. A newer approach is the progressive design-build methodology, in which utilities use design-builder qualifications or pre-defined attributes of best value as their selection criteria, and then move through both the design and construction processes in a collaborative way.

Also evaluated by survey respondents was the construction-manager-at-risk (CMAR) approach. Although CMAR delivery involves two separate contracts — one for design and one for construction, the CMAR firm — often referred to as construction manager/general contractor (CM/GC) — provides value with input into the engineer’s design while also providing early cost estimates that can assist the owner in better understanding the project's anticipated cost and process features. Respondents also evaluated lump-sum or fixed price design-build, in which the design-builder presents a price that includes all elements of the design and construction based upon the owner’s description of the project requirements or a conceptual design provided in the procurement documents.

Choosing a delivery method is a case-by-case activity. We’ll probably never see all projects go with one of the options noted above, but there seems to be increasing interest and usage of the newer, progressive design-build approach. Survey results show that 70 percent of water providers have used the DBB delivery method, which comes as no surprise. However, more than half — 52 percent — have also tried the progressive design-build methodology.

In DBB, the utility bids the project out to contractors using design plans and specifications, and the company that wins the contract handles all construction management details for a set price. The construction-manager-at-risk approach is like DBB, except the contractor delivers the project without exceeding a guaranteed maximum price (GMP). The GMP is based on the design specifications, plus reasonably inferred tasks or additional items, and the contractor is generally selected on qualifications and not on the lowest price.

Since most water utilities are public entities, they’re generally subject to low-bid laws, which means they must take the lowest bidder for those DBB contracts. Project owners are relying on the initial drawings and specifications and trusting that they continue to reflect the actual needs once the construction begins. That may, or more likely may not, be the case. What often happens is that once the facility is up and running, if there are problems, the utility has little leverage to hold the contractor accountable for fixing issues.

This problem arises with CMAR contracts, too. In all these approaches, the designer is always incentivized to come in with the lowest price. Often, the hiring authorities think they’re still getting a value-based deal. They’re not. Even worse, there are many times when something goes out to bid when the design isn’t entirely done. Because contractors are incentivized to offer low bids, they’ll often assume the least, not the most expensive approaches. Project owners frequently are disappointed because they went into the contract thinking they had the documentation necessary to get what they wanted and then find out they didn’t.

In the newer delivery model — the progressive design-build approach — utilities have a single entity designing and constructing the new facility, and they’re not subject to low-bid laws. Instead, utilities can do a best-value selection, and they pick the design-builder largely based on qualifications, not price. Then the design-build entity — a team of a designer and a contractor or an integrated designbuilder — and the utility work on developing the project specifications, plans, budget and timeline collaboratively.

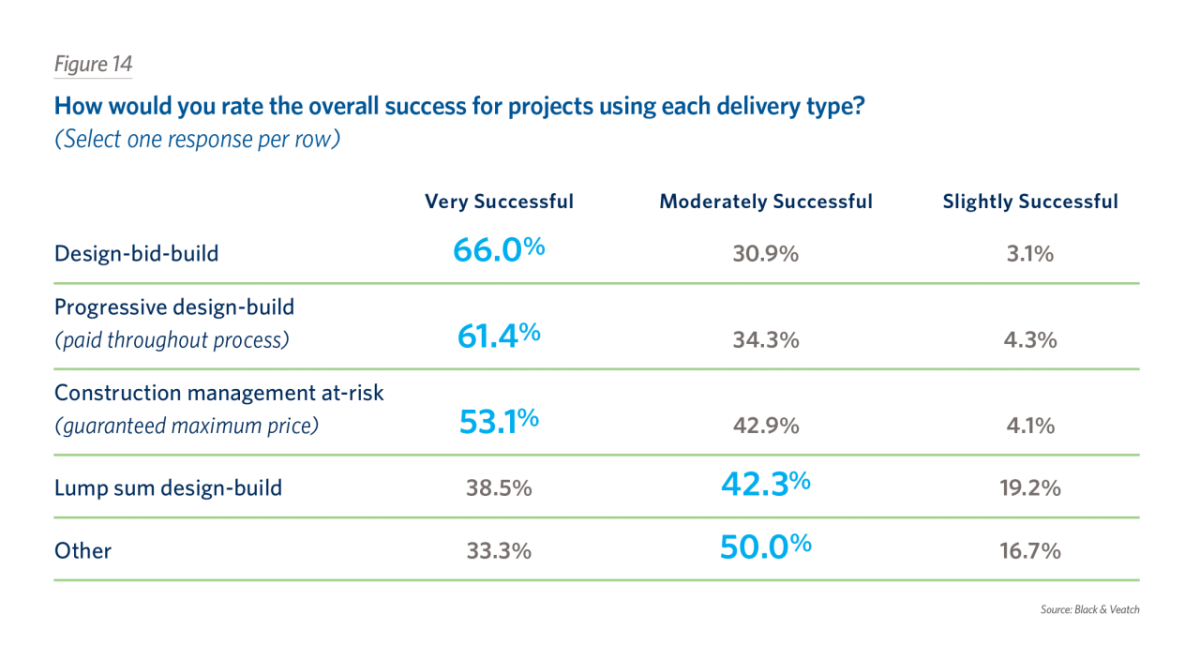

Both DBB and progressive design-build approaches earn generally good evaluations from those water providers who’ve used them. Two-thirds of survey respondents rated DBB projects very successful, and 61 percent said the same for progressive designbuild

projects. The construction-management-at-risk approach earned a “very successful” thumbs up from 53 percent of respondents.

Of these approaches, the progressive design-build delivery method often gives utilities more innovative designs because it’s not based on the lowest bidder, which tends to prompt engineers to be conservative for two reasons: First, the engineers are targeting

lowest-cost, tried-and-true solutions; and, second, if some new approach doesn’t work, it will likely wind up with fingers being pointed in the engineers’ direction.

In contrast, the progressive design-build process tends to be more collaborative, with engineers

and their water-utility clients working together as one. This, too, erodes the decades-long culture of conservative design approaches. In addition, utilities have more control over the process because they can design certain aspects of the project in parallel with construction, allowing problems to be addressed on an ongoing basis. Plus, this delivery method allows water providers to set a budget and have the design-builder work backward to meet the budget. Finally, the mechanism still provides for performance, scheduling and price guarantees, making it an increasingly attractive option.

Asked what delivery method they’d avoid, only 14 percent of respondents picked the progressive design-build approach. That’s twice as many as the number that would shun DBB project delivery, but it’s still notable given the newness of this approach.

Bread and Water

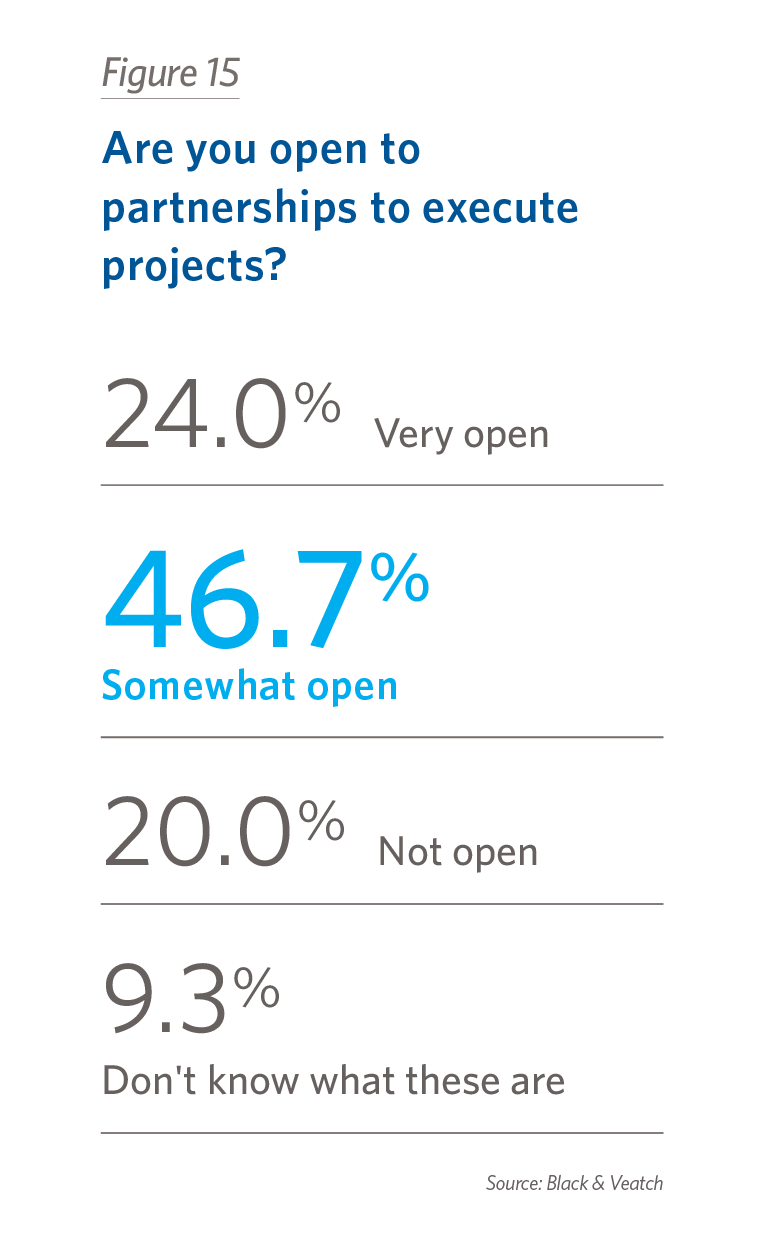

Finding the money is part of the construction process, so the Black & Veatch's 2019 Strategic Directions: Water Report survey asked survey participants if they’d be open to public-private partnership (P3) arrangements. Overall, responses showed that utility staff are open-minded, with 71 percent being somewhat or very open to this funding option. It, like any other project delivery choice, must be determined on a project-by-project basis.

As it turns out, the predominance of aging infrastructure in use will give water providers opportunities to evaluate all the project delivery options: There’s a lot of infrastructure building ahead, and survey results show that water providers will examine all the delivery approaches to get their jobs done.