Occupational Health & Safety: Can New Metrics Stop ‘Safe-Washing’?

The updated GRI OHS Standard looks at damage and recovery from injuries, not lost time

Safe and healthy working environments are crucial for sustainable development, and as such, are one of the targets under the Sustainable Development Goals. According to ILO estimates, around two million people die every year as a result of work-related accidents or diseases, and there are more than 300 million accidents every year. “The suffering caused by such accidents and illnesses to workers and their families is incalculable,” writes the ILO.

Companies have been reporting on work-related injuries for many years, but the metrics most commonly used are outdated and misleading, leading to what experts have dubbed safe-wash. The updated GRI Occupational Health and Safety Standard has redefined how companies measure and report work-related injuries, aiming to make their data more reflective of the impact that these injuries have on workers’ health and safety.

Dr. Sharron O’Neill, an associate professor in the Business School at the University of New South Wales in Canberra, Australia, chaired the expert Working Group that developed the standard. “Safewash is when companies present information that makes them look good, but when you look closer, the information is quite misleading. We see this a lot with reporting on health and safety using lost time injury rates. It is not always deliberate, but it is often misleading” said Dr. O’Neill.

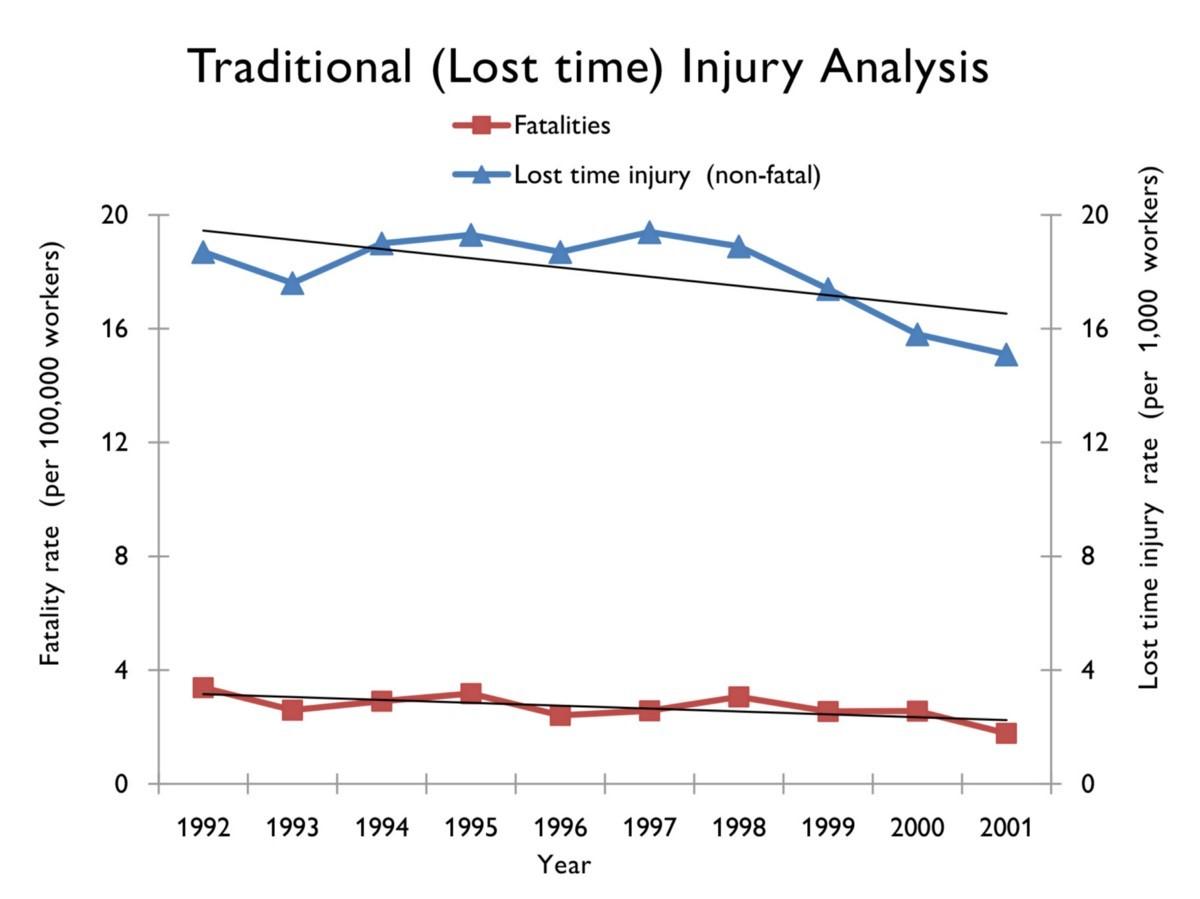

The frequency and severity of work-related injuries has traditionally been assessed using metrics based on lost time or lost work days — the lost-time injury frequency rate (LTIFR) is a classic example of this. One of the problems is lost time incidents don’t catch all injuries that have a significant impact on workers’ health and the way they are calculated hides disabling, but non-fatal, injuries.

As Dr. O’Neill explained, “I think injury reporting has been done so poorly for so long,” she said. “We’ve had decades of reliance on LTIFR; it’s a measure that’s become so entrenched and has become counterproductive because people don’t understand what it is measuring. If they did, they would realize that it’s not actually telling them very much.”

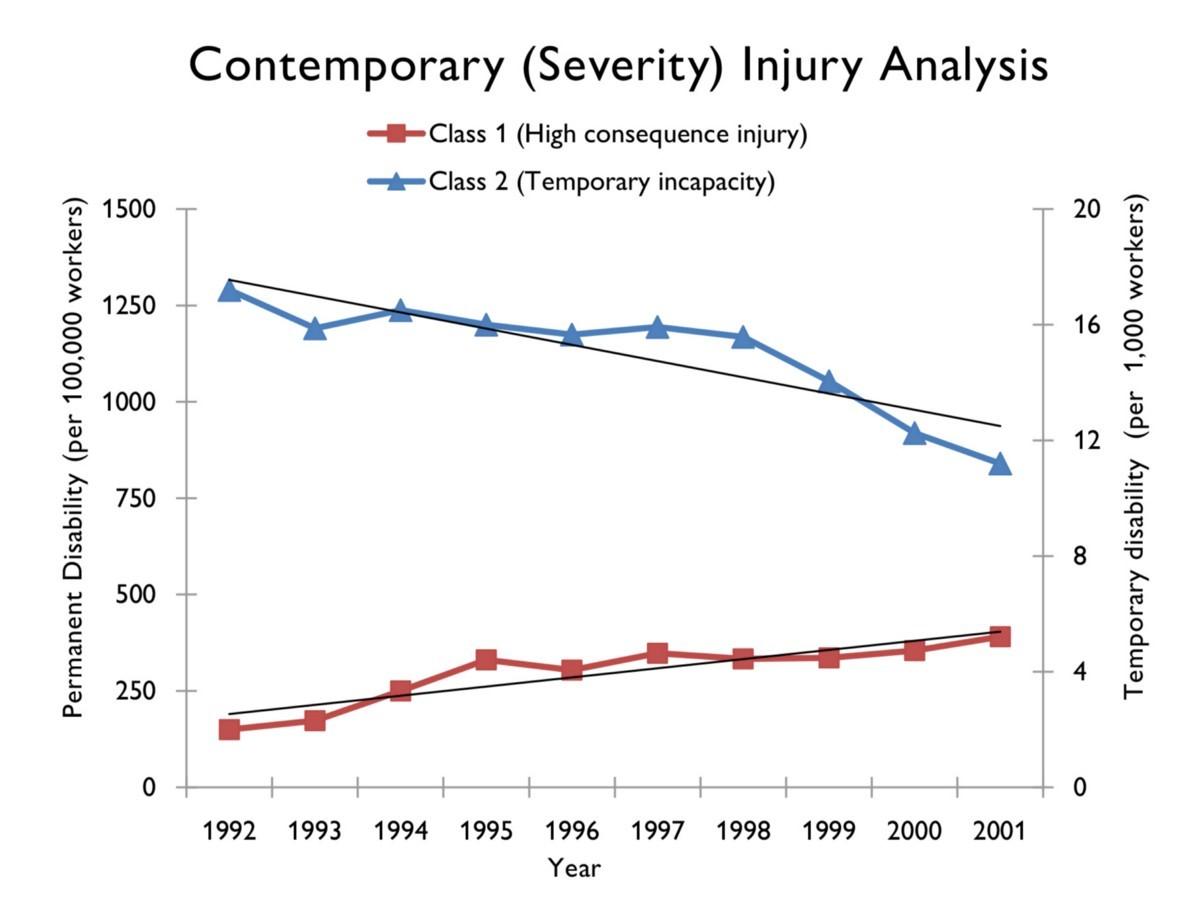

A research paper she co-authored compared a sample of more than 400,000 compensated injuries occurring over a 10 year period, first showing trends in the rate of injuries when claims were classified as either lost-time injuries (LTIs) or fatalities and then when the same injury claims were classified as either permanently disabling or temporary impairment (see below). The two injury frequency graphs presented very different pictures of workplace safety — if injuries are only classified as LTIs and fatalities, readers are uninformed about whether the number of injuries that damage people for life is increasing or decreasing.

Another study then looked at occupational injury performance measures reported publicly by Australia’s 50 largest listed firms between 1997 and 2009. The authors compared changes in the metrics companies chose to report over time, observing a systematic reduction over time in transparency about high-consequence injuries. By focusing only on highly aggregated measures of recordable or lost time injury, companies can manipulate investor perceptions of both occupational safety risk and harm.

This is an issue experts addressed when they were reviewing GRI 403, the Occupational Health and Safety Standard. The result is two new metrics that shift the focus from lost time to recovery time, putting the worker at the heart of the assessments.

Updating the Occupational Health & Safety (OHS) Standard

Like all GRI Standards, GRI 403 was revised through a transparent and inclusive process, following a due process protocol and overseen by the Global Sustainability Standards Board (GSSB), GRI’s independent standard-setting body. A multi-stakeholder Working Group, made up of leading experts from labor, civil society, the investment community, business, and international and governmental institutions from around the world, developed the content.

The focus of the GRI Standards is on companies’ impacts outwards — in this case, companies’ impacts on the health and safety of workers, not how work-related injuries affect the business (such as loss of productivity or compensation costs). With that in mind, the Working Group members proposed metrics to help companies communicate better about their impacts on the health and safety of workers. An important part of this is communicating when injuries have had severe consequences for the workers — something that isn’t reflected in lost-time injury rates.

Lost-time injury rates look at injuries that have resulted in lost working time. This means they only capture cases where people who have an injury report it, and lose at least one shift due to that injury. They also don’t show whether workers have recovered from the work-related injury by the time they return to work; or if they will never recover.

For example, a worker who has suffered a sprained ankle as a result of a work accident might be off work for a couple of days, while another who suffered permanent hearing loss might not register any time off work, but still has a significant work-related injury. Timing also plays a role: if the ankle injury happens on a Friday afternoon there might be no lost working time as the person could recover enough over the weekend to return to work the following Monday, whereas if it happened on a Monday morning, the person might miss a day or two of work.

To address this, the new standard requires organizations to report the number and rate of all injuries using the globally recognizable definition of ‘recordable injuries’ (based on the methodology provided by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration in the United States). These include any injury that results in death, days away from work, restricted work or transfer to another job, medical treatment beyond first aid, or loss of consciousness; or any significant injury diagnosed by a physician or licensed healthcare professional, even if it does not result in any of those things. This addresses the concerns over incomplete reporting of injury frequency because companies need to report all damaging injuries for workers even if they don’t result in days away from work.

Companies need to report all damaging injuries for workers even if they don’t result in days away from work.

Workers may be deemed fit to return to work even if they have not yet fully recovered from a work-related injury, or they may feel pressure to continue working. This means the number of days away from work may not indicate the severity or extent of harm suffered by workers.

Through various discussions, the Working Group explored how best to drive a shift from measuring lost working time to measuring recovery time when assessing the severity of injuries — that is, the time needed for a worker to recover fully to pre-injury health status, as opposed to the time needed for a worker to return to work. Moreover, they looked for a way to discern between those injuries from which workers will quickly and completely recover and those injuries that have higher consequences for workers.

“Companies really need to be asking, ‘Are we injuring people?’ If they are injuring people, they need to be able to identify and assess that in a meaningful way. That’s moving away from measures that focus on the workplace and recognizing instead the need to assess the consequences of OHS incidents for our workers and their families by extension. This requires a concrete, reliable, comparable way of distinguishing between injuries of different levels of severity.”

A new metric to measure injury severity

Classifying injuries in terms of severity is not as simple as it may seem — terms like ‘minor’ and ‘serious’ injury can be very subjective and the severity profile changes on a case-by-case basis. The Working Group therefore had to identify a reliable way of classifying injury severity in order to develop a meaningful metric. Clearly, cases of permanent disability, such as the loss of a limb, are high consequence events. The challenge was to classify the severity of less obvious cases.

Prior research, existing practice and stakeholder consultation together suggested that if it took longer than six months for a worker to recover from injury, it is highly probable that they will suffer long-term or permanent consequences; this set six months as a threshold for determining whether an injury is high-consequence, which can be considered a severe injury for the worker.

“We need to be able to separate those injuries from which a worker can recover fully in a few days, from those that have a longer term effect on the person’s day-to-day life, even if they’re back at work,” explained Dr. O’Neill. “For example, the person may continue to experience pain, loss of mobility or movement, or have wounds that are still healing. Research into compensated injury suggests that if you have not recovered by the time you get to the six or seven-month mark, then you are unlikely to fully recover.”

The experts adopted the concept of ‘high-consequence work-related injury’ — an injury that results in a fatality, or an injury from which the worker cannot recover, such as the amputation of a limb, or from which they do not, or are not expected to, recover fully to pre-injury health status within six months, such as a complex fracture.

How companies can use the new metrics

For many companies, this represents a new way of thinking about injury. According to Dr. O’Neill’s research, there are two main reasons companies don’t report on this information already: some may want to hide their high-consequence injuries, but many others don’t realize it was important or even possible to measure them differently. With the updated GRI OHS Standard, companies have the metrics they need to be transparent about their work-related injuries; to better understand and improve their performance and better inform their stakeholders, including investors.

“I’ve certainly had very positive responses when I explain this to investors and to people who are using the information in annual reports to make decisions. They’re trying to understand the risk exposure of the companies they’re dealing with, and while injury rates don’t measure risk, they can point to gaps in risk management. Being able to assess a company’s OHS impact on workers is, I think, one important step forward in that regard,” Dr. O’Neill said.

The updated GRI 403 standard aims to help companies better describe and understand injury outcomes. Dr. O’Neill stresses that companies should be clear on what the metrics are actually telling them and the benefits of having better quality data at their fingertips. “My advice would be to be realistic. Ignore the temptation to underreport injuries or underestimate their severity — incomplete or poor quality data won’t help anyone make better decisions.”

“I would really like to see companies reporting injury outcomes far more transparently and consistently,” she added. “I think there is a growing global awareness of the benefits for both companies and stakeholders and I’m hopeful that this will improve. I’m very much looking forward to seeing what comes out in the next few years as companies start to get behind the new Standard.”

The GRI 403 Occupational Health and Safety Standard was updated and aligned with internationally-agreed best practice and key instruments in the field. Read more about the development of GRI 403: Occupational Health and Safety, and download the Standard.

- This article originally published on GRI's Medium site