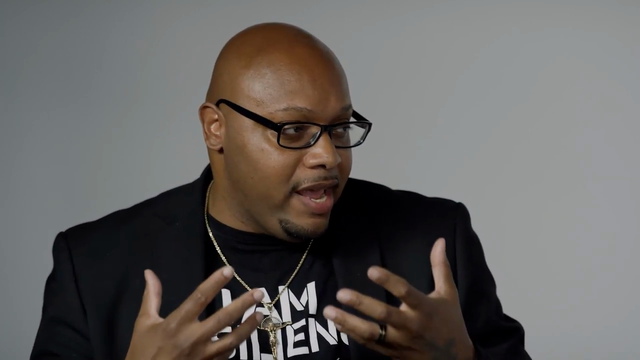

Proving Innocence: Koch Pro Bono Initiative Lends Unmatched Support to Midwest Innocence Project

The State of Missouri sentenced Ricky Kidd to life. The Midwest Innocence Project helped him take it back.

On March 24, 1997, an injustice was committed against Ricky Kidd. The 21-year-old was robbed of his freedom when the State of Missouri convicted him of a double homicide he didn’t commit. The jury’s words hung heavy as they crossed the courtroom that day in March. His sentence: life without the possibility of parole.

“It sounded like I was in a movie,” Ricky says. “Tears were streaming down my face, and I could not fully process it, to be honest.”

While Hollywood could produce a compelling film about Ricky’s story, this was no movie. Ricky's wrongful conviction led to 23 years of incarceration in a maximum-security prison.

“The first two years, I was in a very dark space,” Ricky admits, “and I did not know how to come out of it. I had to come to a point where I had to realize it was either fight or flight. I would make myself repeat, ‘I’m gonna be a victor and not a victim.’ And so, it was enough to pull myself out of it.”

He took up writing, both as a creative outlet and as a way to express his innocence. He wrote pages and pages of poems and plays, but also letters to churches, organizations, lawyers and the media. “Although I would never get a response,” he says, “it was therapeutic because I was doing something about it. Writing helped me put those emotions in a place outside myself.”

Then, one day in 2005, he received a response from the Midwest Innocence Project – a not-for-profit organization based in Kansas City that works to exonerate people wrongly convicted of crimes. While estimates vary, it's reported that approximately 20,000 individuals incarcerated in America are wrongly convicted; some estimates indicate the number could be as high as 10% of the prison population, or about 230,000 people.

“Ricky’s case was one where you looked at it and you just sort of went, ‘How did we end up here?’” says Tricia Bushnell, executive director of the Midwest Innocence Project. “The more in depth you go, you see he had ineffective counsel who didn’t show all of the evidence about the real perpetrators and also didn’t fully establish his alibi.”

After receiving his letter, the Midwest Innocence Project began the tedious process of case review; officially taking on Ricky’s case in 2007. Another two years would pass before Ricky would make his first appearance in a courtroom to fight for his innocence – a losing effort time and again. Hope was all that sustained him through 11 more court appearances and 10 more losses. But, on August 15, 2019, he got the news he’d been hoping for.

“I waited 23 years to hear the words that I was free to go and that I was indeed innocent, and it was finally happening,” Ricky says. “I could barely hold it together. It was the best moment of my life.”

HOW KOCH IS HELPING

Established in 2000, the Midwest Innocence Project covers five states: Kansas, Missouri, Arkansas, Nebraska and Iowa. The organization estimates a backlog of hundreds of cases awaiting review. Each review can contain thousands of pages of documents and take up to a year to complete. Assistance with casework is a constant and vital need.

The Midwest Innocence Project relies on qualified volunteers – the “MVPs,” as the organization refers to them – to help. Those volunteers sift through thousands of pages of police reports, witness interviews, lab reports, trial transcripts, and sometimes numerous appeal and habeas corpus briefs and opinions to help make informed decisions on cases to further investigate and represent.

In 2019, as part of Koch’s Pro Bono Initiative, Koch engaged the Midwest Innocence Project and invited Tricia to visit its Wichita campus to train Koch volunteers in the organization's case file review process. Since then, the number of Koch volunteers has taken off. Ninety-six Koch employees, plus more than 40 attorneys from partner firms, are working on case file reviews. Nearly every Koch business is represented and employees across two continents are involved.

“It’s awesome that we have so many volunteers from Koch and our partner firms who have already been assigned at least one case,” says Tresa Boline, coordinator for the Koch Pro Bono team. “Several have submitted their final case reviews and are excited to get a new one. I never get tired of getting emails or chats from people wanting to know how they can get involved.

There’s no shortage of casework awaiting Koch volunteers working with the Midwest Innocence Project. Some cases Koch employees have taken on have been awaiting review since the early 2000s; others are so complex they require teams of Koch employees to conduct the review. Currently, 41 active case file reviews are underway by Koch volunteers. They have completed and submitted another 19.

“Koch is by far our largest set of volunteers who do this work,” Tricia adds. “They go in, they dive into these documents, they help us understand really what happened and what would be the potential next steps we could take.”

STILL WORK TO DO

Though the work is hard and time-consuming, and oftentimes emotionally draining, Tricia never loses sight of its importance to the men and women currently serving time for crimes they did not commit. “If we make the system so hard that incredibly specialized, trained lawyers can’t win, how is this person going to have hope?”

And that’s exactly what still keeps Ricky Kidd up at night, more than two years removed from the Western Missouri Correctional Center: the knowledge that someone, somewhere, is serving time for another person’s crime, and losing hope. That knowledge drives his passion for being a voice for the voiceless.

Today, Ricky Kidd’s involvement with Midwest Innocence Project isn’t limited to being an exoneree – he also works to free others caught in the same system that failed him 24 years ago. As the organization’s community engagement officer – his website headshot now among the same faces who helped exonerate him – he is responsible for outreach and galvanizing new volunteers around the mission. It's a mission that brought him to Koch Industries' campus this year. His new role has provided him a platform to speak about wrongful convictions from firsthand experience, and on behalf of the thousands of innocent people wrongfully locked behind bars.

“It’s been rewarding and an honor to work for such an organization, but to also be out front communicating with the media and communicating with our volunteers about this important issue,” Ricky says. “It feels right. It feels like my pain and everything I went through has grown and shaped me for this opportunity, and I’m taking full advantage of it.

“It’s important work,” he says, “because it’s not just the individual who is suffering, it’s their family. But it doesn’t stop there. It’s also the community that suffers because when the wrong person is in prison, that means the real criminal is out free in society.”

Tricia’s biggest dream is for everyone working and volunteering with the Midwest Innocence Project to ultimately “work ourselves out of a job” in exoneree advocacy – to create a system where such services are no longer necessary. But while she admits she doesn’t expect to see that day come in her lifetime, the system is changing, and there’s something very simple anyone interested in furthering this cause can do.

“I think one of the biggest things is really education and understanding how hard the process is, and knowing who is deciding justice in your jurisdiction. That is my number-one question to everyone, ‘Do you know your prosecutor? Do you know your attorney general?’ Those are the folks who decide what justice is in your jurisdiction. And so, if you learn about these things, or if you care about how justice is decided, you need to know who those people are.”

As Tricia says, “You don’t have to be a lawyer to care about justice.”

Learn more about the work Ricky and Tricia continue to do, and how you can get involved, at themip.org.