Honoring the Legacy of Artist and Activist Romare Bearden

Stunning sculpture highlights Bearden’s pioneering path

Charlotte’s newest public art – a swirling sculpture to make the city fall in love with a native son all over again – thrusts a gentle steel spear point into the sky above Romare Bearden Park.

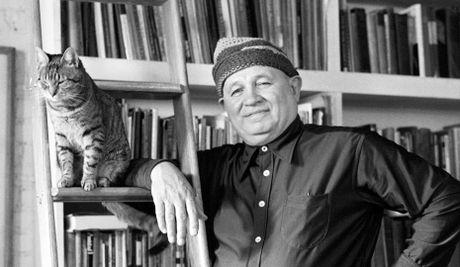

The name “Spiral Odyssey” is a triple tribute. It honors Bearden, the master collage maker who co-founded the New York group Spiral in 1963 to encourage African-American artists. It refers to Homer’s “Odyssey,” which Bearden explored multiple times in his work. And it hints at the two-decade friendship between Bearden and Chicago sculptor Richard Hunt.

The piece can be called abstract, but your mind shapes bits of it into figures: the ship’s body, its billowing sail (or is that a wave?), perhaps a leaping dolphin. Hunt crafted slender arcs of steel so that light falling on them appears to ripple, like a current passing across water.

“Odyssey” has become a selfie magnet for people who encounter it along Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard. No plaque identifies it, though one will appear before the free public dedication Sept. 23 by the Arts & Science Council of Charlotte-Mecklenburg. (Hunt plans to attend, 11 days after his 82ndbirthday.)

Even then, visitors won’t realize it was originally supposed to have taken a different shape … in a different part of the park … from the hands of a different sculptor.

The park is itself a work of art designed by Seattle planner Norie Sato and the local firm LandDesign. The ASC and Mecklenburg County wanted to install a defining centerpiece. It invited a handful of artists to apply and raised $305,000 from a county fund for public art, Duke Energy, the ASC board of directors and grants from the National Endowment for the Arts and North Carolina Arts Council.

A Richmond artist became the front-runner. But “her design was considered a habitable structure: People could go inside it, so it couldn’t be used,” said Carla Hanzal, the ASC’s vice-president of public art.

The council turned to Hunt, whose first design suggested a slave ship, a church and a vertical, Eiffel Tower-like form. “My thought was that it could be interactive, so one could walk through it,” Hunt said. “But it was going to have that same ‘habitable structure’ problem, so I modified it.”

Then a literal stumbling block appeared.

“It was going to go in the center of a main walkway, near the waterfall, and there was a trench drain,” he said. “I thought, ‘Somebody with heels could get stuck in that drain, have an accident, and there might be liability.’ I had just seen a photo of Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge, being helped out of a drain by Prince William and their attendants. I doubted the fashionable ladies of Charlotte would have had such assistance at the ready had there been a similar occurrence in Romare Bearden Park.”

So “Spiral Odyssey” moved to the south side of the park, mounted on a pedestal that keeps it safe from passersby and passersby safe from it. Duke Energy Foundation president Cari Boyce knows it’s in the right place: After stressing Duke’s commitment to culture for a diverse community, she said, “Now when anyone visits Romare Bearden Park, they’ll see ‘Spiral Odyssey’ and have the opportunity to learn about and be inspired by the pioneering path plowed by Bearden.”

Hunt chose stainless steel “because it doesn’t require much in the way of maintenance, and because of the way it reflects light. You can take a sander in the final finishing, after you grind down the weld beads, and kind of draw with it. Movements you make across the surface will be reflected by light, which can change through the day. I have a piece on the river in St. Joseph (Michigan) that reflects the colors of the sunset.” (He has a small studio in Benton Harbor, right across the St. Joseph River, as well as his main workplace in Chicago.)

The Museum of Modern Art gave Hunt and Bearden concurrent exhibitions in 1971. They’d already met in Pittsburgh in the late 1960s when an International Exhibition at Carnegie Museum of Art showed their work.

“I wasn’t part of Spiral; those were people like Bearden who were older than myself. But it had an impact,” Hunt said. “There was a lot of discussion about the civil rights movement, how abstraction or avant-gardism fit in with African-American artists’ responses to life.”

Hanzal curated “Southern Recollections,” the 2011 Bearden show at Charlotte’s Mint Museum that celebrated the 100th anniversary of his birth in Charlotte. She sees similarities between the artists’ approaches: Both improvise, leaving themselves freedom to discover their subjects as they go. Hunt has made other versions of “Spiral Odyssey” and likes “to leave all the possibilities open as long as I can. I want to let the work, as it’s being developed in full scale, suggest things beyond what was anticipated in the model.”

Both also make immediately accessible art, even when using abstract elements. Charlotte’s public pieces frequently get mocked, though they may later be beloved. (Think of Niki de Saint Phalle’s “Firebird” on Tryon Street). But “Odyssey” has had clear sailing.

“It’s rare for public art not to draw any negative comments, but this hasn’t,” Hanzal said. “That’s a tribute to his skill.”